Various degenerative conditions can affect the vitreous body and the retina, although the intimate function of these two structures often creates difficulties in determining which tissue is affected first in the pathological process.

Under the term 'vitreo-retinal degenerations' are grouped those pathological situations in which alterations involve both structures.

Vitreo-retinal degeneration can be of hereditary origin 'hereditary vitreoretinopathies' (Tab. I) or acquired "haloidoretinopathies".

The latter (Tab. II) can be either related to the ageing of the vitreous (vitreous syneresis e vitreous detachment), either secondary to the presence of extracellular, protein deposits (vitreal amyloidosis) or lipid (vitreopathyasteroid e sparkling synchysis).

Three clinical conditions commonly referred to as degenerative vitreopathies are discussed in this chapter:

The term degenerative vitreopathy is, however, a misnomer (1) since it implies a primary process at the level of the vitreous gel, whereas the only primary degeneration of the vitreous is syneresis and vitreous detachment, whereas most degenerative vitreopathies are secondary to retinal degeneration and the material that accumulates in the vitreous comes from structures other than the vitreous, although this has not yet been conclusively demonstrated in the case of asteroid vitreopathy.

ASTEROID VITREOPATHY

Asteroid degeneration of the vitreous was first described by Schmidt (2) and was differentiated from scintillating synchysis by Benson in 1894 (3). The variants proposed by Wiegmann can still be found in the European literature (4): 'Scintillatio nivea' e "scintillatio albescens'.

Asteroid vitreopathy is a rare condition, with a prevalence in the general population between 0.15% and 0.9% (5).

Unilateral in 75% of cases, it is generally found in individuals over 60 years of age and is more frequent in diabetics.

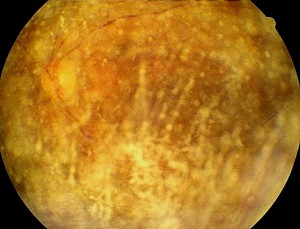

Clinic. The characteristic appearance of asteroid vitreopathy is represented by the presence of shiny, yellowish-white round opacities suspended in the vitreous gel (Fig. 1), often aggregated in clusters and resembling strings or clusters of pearls.

The vitreous has a normal appearance: vitreous liquefaction and DPV are only present in 12% of subjects (6). The asteroid bodies are attached to the collagen fibres and are mobile with the movements of the vitreal gel. On ultrasound examination, a multitude of hyperechogenic peaks are observed, which are mobile with the movement of the eyeball. A constant feature is the presence of a hypoechogenic vitreal corona between the hyper-reflective image of the asteroid bodies and the anterior surface of the retina, which can be confused with a posterior vitreous detachment.

Asteroid vitreopathy is generally asymptomatic. Even if the opacities are so dense that they obstruct vision of the ocular fundus, patients do not have a reduction in visual acuity and the disease is often a fortuitous discovery during a routine eye examination.

When significant visual impairment is present, an associated retinal pathology must be suspected (age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, etc.).

Histopathology. Transmission electron microscope analysis revealed the presence of complex lipids and X-ray diffraction analysis showed that the asteroid particles are formed by the apposition of concentric layers of phospholipids associated with calcium-phosphate complexes, which are intimately bound to the vitreous collagen (6).

Aetiology. The aetiology still remains unknown.

No associations with other ocular or systemic pathological conditions have been demonstrated (7): the link with diabetes mellitus, reported in some initial studies (8), was later cast into doubt due to methodological shortcomings in the research carried out (9).

Furthermore, no study has reported the association of asteroid hyalopathy with hereditary dyslipidosis.

Treatment. Asteroid degeneration rarely requires therapeutic treatment because it is usually asymptomatic and free of complications (10).

In rare cases where a massive concentration of asteroid bodies is present in the central part of the vitreous cavity, a discrete visual impairment may occur.

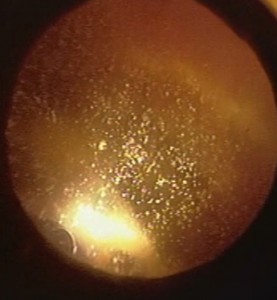

Poor visibility of the ocular fundus sometimes does not allow surveillance of posterior segment pathology and possible retinal photocoagulation. In such cases, a vitrectomy via pars plana (10-14) may be proposed (Fig. 2).

However, vitrectomy in asteroid degeneration is not risk-free (1, 11, 15) and may even favour postoperative retinal detachment. This complication probably occurs because posterior vitreous detachment and vitreous liquefaction are significantly less frequent in this disease than in the normal population of similar age (p<0.01), while vitreoretinal adherence is greater (1).

SPARKLING SYNCHYSIS

Sparkling synchysis is a degenerative condition of the vitreous often confused with asteroid vitreopathy, from which it must be differentiated both clinically and pathologically.

Clinic. First described by Sichel in 1846 (16), it presents clinically as minute multiple crystalline, shiny and coloured particles suspended in a degenerated and liquefied vitreous (17).

The appearance of these corpuscles is flat and angular, in contrast to the rounded appearance of asteroid bodies.

The crystals are mobile with the movements of the eye, but independent of the movements of the vitreous, unlike the asteroid bodies that are structurally associated with the vitreous.

During eye movements, they spread rapidly in the vitreous cavity as multicoloured confetti, but settle by gravity on the ocular fundus when the eye is motionless.

In phakic patients, particles can accumulate in the anterior chamber (Fig. 3) and simulate a hypopyon (18, 19). Sometimes secondary glaucoma can develop (18, 19).

The echographic appearance corresponds to a multitude of medium echogenic points.

Sparkling synchysis is most often found in individuals under 35 years of age (20), while asteroid hyaloidopathy occurs in the elderly.

Scintillating synchysis occurs exclusively in severely traumatised or chronically inflamed eyes (17) or following intravitreal haemorrhage (21).

Histopathology. Histopathological studies have further differentiated scintillating synchysis from asteroid vitreopathy. The crystals of the synchysis, in fact, consist of cholesterol crystals, whereas the asteroid bodies are composed of a calcium-phospholipid complex (22). This is why the most appropriate term for this condition would be 'cholesterosis bulbi'.

Aetiology. The exact aetiology of cholesterol crystals is unclear. Cholesterol most likely results from the cellular destruction of red blood cells or lysed leukocytes from haemovitreous or chronic inflammation (22).

Treatment. The presence of cholesterol crystals in the vitreous chamber does not require any treatment; however, aphakic patients with this condition may develop glaucoma when the particles obstruct the filtering angle. In these cases, a vitrectomy and washing of the anterior chamber is useful.

VITREAL AMYLOIDOSIS

Amyloidosis is a disease characterised by the extracellular deposition of an abnormal protein substance that exhibits distinctive dye, biochemical and ultrastructural features. The abnormal protein is a prealbumin, dependent on a mutation at the transthyretin level.

The pathogenesis of this complex disease remains obscure.

The current anatomo-pathological classification distinguishes amyloidosis into systemic (polyvisceral) or localised (monovisceral), primary or secondary, familial or idiopathic (23).

Ocular localisations are multiple and can affect the oculo-motor muscles, lacrimal gland, eyelids, conjunctiva, cornea, vitreous, retina and orbit.

Although amyloidosis as a disease in its own right was recognised as early as the beginning of the 19th century, vitreous involvement was not observed until 1953 (24).

Clinic. Vitreous changes are mainly found in hereditary-family amyloid neuropathies type I and II and may represent the first manifestation of the disease, arising long before the involvement of other organs.

They present clinically (23, 25, 26, 27) as whitish deposits in contact with the retinal vessels, particularly around the arterioles, simulating the appearance of a cottony exudate.

The density of the amyloid deposits increases progressively to the point of covering entire sections of retinal vessels. The opacities subsequently extend into the vitreous cavity to form granular aggregates with slightly frayed edges that spread posteriorly and attach to the posterior face of the lens in the form of whitish opacities with pseudopodia, taking on the appearance of 'lace veils' or 'glass wool'. This bilateral and symmetrical appearance is specific to the disease.

Vitreous amyloidosis is often asymptomatic. Visual impairment occurs when vitreal opacities are dense or accumulate at the level of the posterior capsule of the crystalline lens.

Rarely associated with complications, however, the amyloid substance may constrict and obliterate choroidal and/or retinal vessels and lead to peripheral retinal neovascularisation and vitreous haemorrhage (28).

In the developmental form, open angle glaucoma can develop secondary to the presence of amyloid deposits in the trabecular meshwork. Secondary glaucoma can also arise due to increased episcleral venous pressure in the case of an amyloid lesion of the episcleral veins (29).

Treatment. The only form of treatment for vitreal amyloidosis is vitrectomy via pars plana (26, 30-33). The operation is indicated when vitreous opacities cause significant visual impairment.

Vitrectomy must be complete and above all retrolental, because recurrences are generally due to vitreous remaining behind the lens.

If a posterior vitreous detachment is present, the prognosis is favourable. If, on the other hand, the vitreous is not detached, there is a risk of iatrogenic retinal haemorrhages and ruptures, and amyloid opacities firmly adhered to the retina cannot be removed.

Prof. Raffaello di Lauro,

Dr Maria Teresa di Lauro,

Dr Raffaella di Lauro,

Dr. Alessandro Senese,

Dr Paola Giustiniani,

Dr Antonietta D'Aloia

CTO Ophthalmology Division - NAPLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1) Schepens C.L., Neetens A. 'The vitreous and vitreoretinal disorders'. Springer-Verlag Ed., Ny, 1990, 109-127.

2) Schmidt: cited by Wiegmann.

3) Benson A.H. 'Diseases of the vitreous. A case of mononuclear asteroid hyalitis'. Trans. Ophthalmol. Soc. Uk, 1894, 14: 101-104.

4) Wiegmann 'Ein beitrag zur genese und zum bilde der synchisis scintillans'. Klin. Mon. Augen, 1918, 61:82-88.

5) Safir A. et al. "Is asteroid hyalosis ocular gout?" Ann. Ophthalmol. , 1990, 22: 70-77.

6) Topilow H. Et Al. 'Asteroid hyalosis. biomicroscopy. Ultrastructure and composition'. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1982, 100: 964-968.

7) Bergren R.L., Brown G.C., Duker J.S. 'Prevalence and association of asteroid hyalosis with systemic disease'. Am. J. Ophthalmol., 1991, 11: 289-293.

8) Smith J.L. 'Asteroid hyalitis: incidence of diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia'. J.A.M.A., 1958, 168: 891-893.

9) Luxenberg M., Sime D. 'Relationship of asteroid hyalosis to diabetes mellitus and plasma lipids levels'. Am. J. Ophthalmol., 1969, 67: 406-413.

10) Feist R.M. Et Al. 'Vitrectomy in asteroid hyalosis'. Retina, 1990, 10: 173-177.

11) Parnes R.E., Zakov Z.N., Ovak M.A., Rice J.A. 'Vitrectomy in patients with decreased visual acuity secondary to asteroid hyalosis'. Am. J. Ophthalmol., 1998, 125: 703-704.

12) Lambrov F.H.Jr Et Al. 'Vitrectomy when asteroid hyalosis prevents laser photocoagulation'. Ophthalmic Surg., 1989, 20: 100-102.

13) Olea Vallejo Et Al. 'Vitrectomy for asteroid hyalosis'. Arch. Soc. Esp. Ophthalmol., 2002, 77: 201-204.

14) Boissonnot M., Manic H., Balayre S., Dighero P. "Indications de la vitrectomie chez les patients atteints d'une baisse d'acuite visuelle secondarie a une hyalopatie asteroide". J. Fr. Ophtalmol., 2004, 7: 791-794.

15) Ikeda T. Et Al. 'Vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy with asteroid hyalosis'. Retina, 1998, 18: 410-414.

16) Sichel J. 'Note Complementaire Sur Le Synchisis Etincellent'. Ann. Oculist., 1846, 15: 248.

17) Wand M., Smith T.R., Cogan D.G. 'Cholesterosis bulbi: the ocular abnormality knows as synchisis scintillans'. Am. J. Ophthalmol., 1975, 80: 177-183.

18) Michiels J., Garin P. 'Synchisis scintillans of the anterior chamber'. Bull. Soc. Belge Ophtalmol., 1969, 152: 455-458.

19) Eke T., Richer R.G. 'Pseudohypopyon to synchisis scintillans'. Eye, 1996, 10: 527-528.

20) Hogan M.J., Zimmerman L.E. 'Ophthalmic pathology. 2nd Ed. Sauders, Philadelphia, 1962, 650-654.

21) Spraul C.W., Grossniklaus H.E. 'Vitreous haemorrhage'. Surv. Ophthalmol., 1997, 42: 3-39

22) Andrews J.S., Lynn C., Scobey J.W., Elliot J.H. 'Cholesterosis bulbi. Case report with modern chemical identification of the ubiquitous crystals'. Br. J. Ophthalmol., 1973, 57: 838-844.

23) Flament J., Storck D. 'Oeil Et Pathologie Generale'. Masson Ed., Paris, 1997, 176-179.

24) Kantarjian A.D., Dejong R.N. 'Familial primary amyloidosis with nervous system involvement'. Neurology, 1953, 3: 399-409.

25) Dhermy P. 'Amylose oculaire'. J. Fr. Ophtalmol., 1987, 10: 91-103.

26) Doft B.M., Machemer R. et al. 'Pars plana vitrectomy for vitreous amyloidosis'. Am. J. Ophthalmol., 1970, 94: 982-991.

27) Monteiro G.J., Martins A.F. et al. 'Ocular changes in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy with dense vitreous opacities'. Eye, 1991, 5: 99-105.

28) Savage D.J., Mango C.A. 'Amyloidosis of the vitreous. fluorescein angiographic findings and neovascularization'. Arch. Ophthalmol., 1982, 100: 1776-1779.

29) Nelson G.A., Edward D.P., Wilensky J.T. 'Ocular amyloidoses and secondary glaucoma'. Ophthalmology, 1999, 106: 1363-1366.

30) Treister G., Gad K. 'Treatment of vitreous opacities in a case of familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy by vitreous surgery'. Metab. Paediatric. Ophthalmol., 1981, 5: 105-108.

31) Irvine A.R., Char D.H. 'Recurrent amyloid involvement in the vitreous body after vitrectomy'. Am. J. Ophthalmol., 1976, 82: 705-708.

32) Sandgren O., Stenkula S., Dedorson I. 'Vitreous surgery in patients with primary neuropathic amyloidosis'. Acta Ophthalmol., 1985, 63: 383-388.

33) Gastaud P., Betis F. 'Modifications degenerative du vitre' in Brasseur G.: Pathologie Du Vitre. Masson Ed. Paris, 2003, 149-155.

Dr. Carmelo Chines

Direttore responsabile