"We see with our eyes, but we also see with our minds" - Oliver Sacks

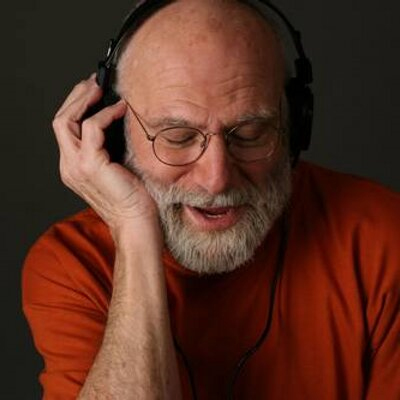

On Sunday 30 August, Dr Oliver Sacks, a great scientist who explored some of the 'places' of the mysterious world that is our brain, left us.

On Sunday 30 August, Dr Oliver Sacks, a great scientist who explored some of the 'places' of the mysterious world that is our brain, left us.

A brilliant neurologist and a man of rare kindness, he was able to realise the unexpressed potential and the many untapped capacities of our minds. This is precisely why he liked to say 'We see with our eyes, but we also see with our minds. And this is often called imagination, ....' (see the video published by Internazionale)

Indeed, in 'The Man Who mistook His Wife for a Hairdo' Sacks wrote: 'Certainly the brain is a machine and a processor, and classical neurology is absolutely right. But the mental processes, which constitute our being and our life, are not only abstract and mechanical, they are also personal; and as such they involve not only classification and ordering into categories, but also a continuous activity of judgement and feeling'. Dr Sacks has been a staunch advocate of the need to communicate with patients and especially 'knew' talk to his patients and instil hope and courage in them, even in the face of the most terrible diagnoses.

As proof of this, he himself wanted to announce to the world that the tumour that had struck him in his liver had spread to his brain and would take it away. And even then he uttered extraordinary words to express his joy at having lived and being able to achieve so many important things during his lifetime.

A courageous and often unconventional man and scientist, who sometimes caused a stir and criticism within the scientific community.

The general public got to know him with the 1990 release of the film 'Awakenings', inspired by his book 'Awakings', published in 1973 and released in Italy in 1987. The film tells the true story of a doctor, Dr Malcolm Sayer (in reality Sacks himself) played by Robin Williams, and his experience with a rare neurological disease, lethargic encephalitis, which condemns patients to a catatonic condition. By experimentally administering L-Dopa, Dr Sayer/Sacks had managed to bring some of them back to a stage of consciousness and contact with reality.

Dr Sacks was also a poet and writer, among his best known books: The Man Who mistook His Wife for a Hat (1986), On One Leg (1991), An Anthropologist on Mars (1995), The Island of the Colourless (1997), Hallucinations (2013). Often, through books, Sacks entered into a relationship with his readers, especially when they were readers/patients. One example for all, reported in the New York Times on the occasion of theobituary of Dr SacksLennerd recounts that he sent a copy of Sacks' 'Musicophilia' to his elderly uncle who suffered from amusia, a neurological disorder in which musical sounds are perceived as a cacophonous set of unpleasant, out-of-tune noises. Lennerd reports that his uncle was 'comforted in knowing that he was not alone and that he was not insane'.

Oliver Sacks, in fact, firmly believed that his mission was to help people 'on the move' to reassure themselves that they were not going mad, not least because for him the boundary between health and mental illness was by no means so clear-cut and defined. There is great anticipation for the publication by Adelphi on 15 October of the Italian version of Sacks' autobiography 'On the move' ('In movimento'). Many passages are bound to reveal to the public the complex personality of a man who is fragile, contradictory, but also generous, optimistic and, above all, full of the will to live. Some brief anticipations: "... I disappointed and disturbed my parents when I confessed to homosexuality as a teenager; I fled to the United States after my brother Michael became psychotic and the air in the house became unbreathable;... I courted death with motorbike speed, extreme bodybuilding and amphetamines; and only when I was kicked out of research labs and began devoting myself to patients did I realise that my life could have a purpose and I never left that lifeline again."

Dr. Carmelo Chines

Direttore responsabile